The Cruel Social Experiment of Reality TV

The new Hulu film about an atrocious moment in ’90s television is shocking, but revelatory.

More than a decade after watching it, I still get twitchy thinking about “White Bear,” an early episode of Black Mirror that stands as one of the most discomfiting installments of television I’ve seen. A woman (played by Lenora Crichlow) groggily wakes up in a strange house whose television sets are broadcasting the same mysterious symbol. When she goes outside, the people she encounters silently film her on their phones or menacingly wield shotguns and chainsaws. Eventually, trapped in a deserted building, the woman seizes a gun and shoots one of her tormentors, but the weapon surprises her by firing confetti instead of bullets. The walls around her suddenly swing open; she’s revealed to be the star of a sadistic live event devised to punish her repeatedly for a crime she once committed but can’t remember. “In case you haven’t guessed … you aren’t very popular,” the show’s host tells the terrified woman, as the audience roars its approval. “But I’ll tell you what you are, though. You’re famous.”

“White Bear” indelibly digs into a number of troublesome 21st-century media phenomena: a populace numbed into passive consumption of cruel spectacle, the fetishistic rituals of public shaming, the punitive nature of many “reality” shows. The episode’s grand reveal, a television staple by the time it premiered in 2013, is its own kind of punishment: The extravagant theatrics serve as a reminder that everything that’s happened to the woman has been a deliberate construction—a series of manipulations in service of other people’s entertainment.

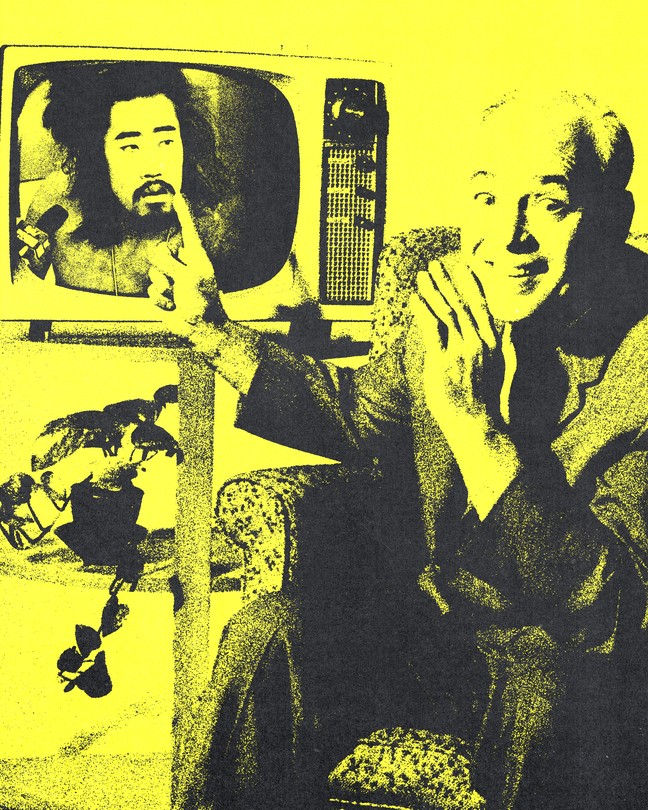

The contrast between the aghast subject and the gleeful audience, clapping like seals, is almost too jarring to bear. And yet a version of this moment really happened, as seen about an hour into The Contestant, Hulu’s dumbfounding documentary about a late-’90s Japanese TV experiment. For 15 months, a wannabe comedian called Tomoaki Hamatsu (nicknamed “Nasubi,” or “eggplant,” in reference to the length of his head) has been confined, naked, to a single room filled with magazines, and tasked with surviving—and winning his way out, if he could hit a certain monetary target—by entering competitions to win prizes. The entire time, without his knowledge or consent, he’s also been broadcast on a variety show called Susunu! Denpa Shōnen.

Before he’s freed, Nasubi is blindfolded, dressed for travel, transported to a new location, and led into a small room that resembles the one he’s been living in. Wearily, accepting that he’s not being freed but merely moved, he takes off his clothes as if to return to his status quo. Then, the walls collapse around him to reveal the studio, the audience, the stage, the cameras. Confetti flutters through the air. Nasubi immediately grabs a pillow to conceal his genitals. “My house fell down,” he says, in shock. The audience cackles at his confusion. “Why are they laughing?” he asks. They laugh even harder.

Since The Contestant debuted earlier this month, reviews and responses have homed in on how outlandish its subject matter is, dubbing it a study of the “most evil reality show ever” and “a terrifying and bizarre true story.” The documentary focuses intently on Nasubi’s experience, contrasting his innocence and sweetness with the producer who tormented him, a Machiavellian trickster named Toshio Tsuchiya. Left unstudied, though, is the era the series emerged from. The late ’90s embodied an anything-goes age of television: In the United States, series such as Totally Hidden Video and Shocking Behavior Caught on Tape drew millions of viewers by humiliating people caught doing dastardly things on camera. But Tsuchiya explains that he had a more anthropological mission in mind. “We were trying to show the most basic primitive form of human being,” he tells The Contestant’s director. Nasubi was Tsuchiya’s grand human experiment.

The cruelty with which Nasubi was treated seems horrifying now, and outrageously unethical. Before he started winning contests, he got by on a handful of crackers fed to him by the producers, then fiber jelly (one of his first successful prizes), then dog food. His frame is whittled down in front of our eyes. “If he hadn’t won rice, he would have died,” a producer says, casually. The question of why Nasubi didn’t just leave the room hangs in the air, urgent and mostly unexamined. “Staying put, not causing trouble is the safest option,” Nasubi explains in the documentary. “It’s a strange psychological state. You lose the will to escape.”

But the timing of his confinement also offers a clue about why he might have stayed: 1998, when the comedian was first confined, was a moment in flux, caught between the technological innovations that were rapidly changing mass culture and the historical atrocities of the 20th century. Enabled by the internet, lifecasters such as Jennifer Ringley were exposing their unfiltered lives online as a kind of immersive sociological experiment. Webcams allowed exhibitionists and curious early adopters to present themselves for observation as novel subjects in a human zoo. Even before the release of The Truman Show, which came out in the U.S. a few months after Nasubi was first put on camera, a handful of provocateur producers were brainstorming new formats for unscripted television, egged on by the uninhibited bravado and excess of ’90s media. These creators acted as all-seeing, all-knowing authorities whose word was absolute. And their subjects, not yet familiar with the “rules” of an emerging genre, often didn’t know what they were allowed to contest. Of Tsuchiya, Nasubi remembers, “It was almost like I was worshipping a god.”

In his manipulation of Nasubi, Tsuchiya was helping pioneer a new kind of art form, one that would lead to the voyeurism of 2000s series such as Big Brother and Survivor, not to mention more recent shows such Married at First Sight and Love Is Blind. But the spectacle of Nasubi’s confinement also represented a hypothesis that had long preoccupied creators and psychologists alike, and that reality television has never really moved on from. If you manufacture absurd, monstrous situations with which to torment unwitting dupes, what will they do? What will we learn? And, most vital to the people in charge, how many viewers will be compelled to watch?

Some popular-culture historians consider the first reality show to be MTV’s The Real World, a 1992 series that deliberately provoked conflict by putting strangers together in an unfamiliar environment. Others cite PBS’s 1973 documentary series An American Family, which filmed a supposedly prototypical California household over several months, in a conceit that the French philosopher Jean Baudrillard called the “dissolution of TV in life, dissolution of life in TV.”

But the origins of what happened to Nasubi seem to lie most directly in a series that ran on and off from 1948 to 2014: Candid Camera. Its creator, Allen Funt, was a radio operator in the Army Signal Corps during World War II; while stationed in Oklahoma, he set up a “gripe booth” for soldiers to record their complaints about military service. Knowing they were being taped, the subjects held back, which led Funt to record people secretly in hopes of capturing more honest reactions. His first creative effort was The Candid Microphone, a radio show. The series put its subjects in perplexing situations to see how they’d respond: Funt gave strangers exploding cigarettes, asked a baker to make a “disgusting” birthday cake, and even chained his secretary to his desk and hired a locksmith to “free” her for her lunch break. “With the candid microphone, we are at the beginning of the Age of the Involuntary Amateur,” one critic wrote in 1947. “The possibilities are limitless; the prospect is horrifying.” Sure enough, a TV series soon followed.

For all that critic’s revulsion, Funt was earnest about the potentially revelatory power of his shows. He was seemingly influenced by two parallel trends. One was a sociological school of thought that was trying urgently to analyze human nature following a wave of real barbarities: the Holocaust, the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Stalin’s great purges. The other was an interest in art that captured the contours of real life, in an outgrowth of the naturalist movement that had come out of the late 19th century. Émile Zola, one of its practitioners, argued in The Experimental Novel that fiction writers were essentially omnipotent forces dropping characters into realistic situations to consider how they might respond. Literature, he argued, was “a real experiment that a novelist makes on man.”

The invention of television, as the academic Tony E. Jackson has argued, offered a more literal and scientific medium within which creators could manipulate real human subjects. This was where Candid Camera came into play. Funt’s practical jokes—setting up a subject in an elevator in which every other person suddenly turns their back to him—tended to consider the nature of compliance, and what humans will go along with rather than be outliers. Candid Camera was considered so rich a work that Funt was asked to donate episodes to Cornell University’s psychology department for further study.

Funt was also highly influential to Stanley Milgram, a social psychologist who turned his Yale studies on conformity into a documentary titled Obedience. The Milgram experiment, conducted in 1961, asked members of the public to inflict fellow subjects with electric shocks—faked, unknown to them—when ordered to do so by an authority figure. Inspired by the 1961 trial of the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann, and the experience of his own family members who’d survived concentration camps, Milgram tweaked the Candid Camera model to more explicitly study how far people would follow orders before they objected. As the film professor Anna McCarthy has written, Milgram paid particular attention to the theatrical elements of his work. He even considered using recordings of humans screaming in real, rather than simulated, pain to maximize the authenticity of the subject’s experience. “It is possible that the kind of understanding of man I seek is an amalgam of science and art,” Milgram wrote in 1962. “It is sure to be rejected by the scientists as well as the artists, but for me it carries significance.”

This studied interest in human nature continued in PBS’s An American Family; its presentation of ordinary life up close, the anthropologist Margaret Mead once argued, was “as important for our time as were the invention of the drama and the novel for earlier generations—a new way for people to understand themselves.” Throughout the later decades of the 20th century, television was similarly fixated on exposure, although shock value quickly took priority over genuine curiosity and analysis. During the ’90s, on talk shows such as The Jerry Springer Show and Maury, people confessed their most damning secrets to anyone who cared to watch. Series including Cops and America’s Most Wanted offered a more lurid, voyeuristic look at crime and the darkness of human nature.

By the time Tsuchiya had the idea to confine a man to a single apartment to see whether he could survive the ordeal, the concept of humiliation-as-revelation was well established. “I told [Nasubi] that most of it would never be aired,” the producer explains in The Contestant. “When someone hears that, they stop paying attention to the camera. That’s when you can really capture a lot.” As an organizing principle for how to get the most interesting footage, it seems to stem right from Funt’s secret recordings of people in the 1940s. Tsuchiya appeared to be motivated by his desire to observe behavior that had never been seen before on film—“to capture something amazing … an aspect of humanity that only I, only this show, could capture.” And extremity, to him, was necessary, because it was the only way to provoke responses that would be new, and thus thrilling to witness.

The reality-show boom of the early 2000s was intimately informed by this same intention. When Big Brother debuted in Holland in 1999, it was broadly advertised as a social experiment in which audiences could observe contestants under constant surveillance like rats in a lab; the show was compared by one Dutch psychologist to the Stanford prison experiment. (Another called the show’s design “the wet dream of a psychological researcher.”) The 2002 British show The Experiment even directly imitated both the Stanford setup and Milgram’s work on obedience. But although such early series may have had honest intentions, their willingness to find dramatic fodder in moments of human calamity was exploited by a barrage of crueler series that would follow. The 2004 series There’s Something About Miriam had six men compete for the affections of a 21-year-old model from Mexico, who was revealed in the finale to be transgender—an obscene gotcha moment that mimics the structure of Candid Camera. Without a dramatic conclusion, a nonfiction series is just a filmed record of events. But with a last-act revelation, it’s a drama.

Contemporary audiences, blessedly, have a more informed understanding of ethics, of entrapment, and of the duty of care TV creators have to their subjects. In 2018, the British show Love Island spawned a national debate about gaslighting after one contestant was deemed to be manipulating another. There’s no question that what happened to Nasubi would trigger a mass outcry today. But reality TV is still built on the same ideological imperatives—the desire to see people set up in manifestly absurd scenarios for our entertainment. The Emmy-nominated 2023 series Jury Duty is essentially a kinder episode of Candid Camera extended into a whole season, and the internet creator known as MrBeast, the purveyor of ridiculous challenges and stunts, has the second most-subscribed channel on all of YouTube. What’s most remarkable about The Contestant now is how its subject managed to regain his faith in human nature, despite everything he endured. But the ultimate goal of so many contemporary shows is still largely the same as it was 25 years ago: to manufacture a novel kind of social conflict, sit back, and watch what happens.